|

March-May 2008

|

BLACK

HORSE EXTRA

Blame It on Sudden Hoofprints

Of Plotters and Pantsers

More Horse Talk New Black Horse Westerns

Convenient distribution

and sales might be a separate matter, but the London home address of the

Black Horse Western line has proved no handicap when it comes to providing

discerning readers with action-packed novels in the best traditions of the

genre.

It may, in fact, have helped. The authors do not have the responsibility

imposed by a western publisher looking for -- as one back-cover blurb

puts it -- "an epic story of the building of our mighty nation". BHWs stick

for the most part to fulfilling expectations similar to those of the readers

who eagerly sought out the western pulps of an earlier era.

This is not to say that BHW readers would look kindly upon an author who

played fast and loose with history and geography, or that many BHW titles

are not written by United States citizens motivated by other than national pride. But primarily the reader who borrows or buys

a BHW is seeking fiction that has been created to entertain. The term "light

fiction" comes to mind, though not used pejoratively as some people these

days would have it.

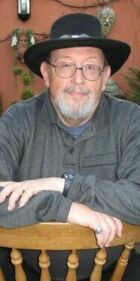

In this edition of the Extra, it's our pleasure to invite you to meet Christopher

Kenworthy (aka Walt Masterson), one of the best of the Britons who have

turned their expert writing hand -- he is another former journalist -- to

the Old West. He tackles the job with a combination of flair and respect.

Like many before him, he has afterwards visited places he has written about

with a degree of trepidation that has fortunately proved unfounded.

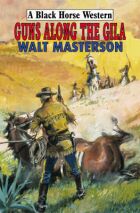

Chris (or Walt) sets his westerns in a piece of country that will be very

familiar to many of his readers at the present time, since it's also the

setting for a string of fine western stories that first appeared in the pulps

and have now been published in The Complete Western Stories of Elmore

Leonard. This 2004 collection of 30 stories by a master writer was

reissued in paperback last year, was a "recommended read" at the Saddlebums

Western Review blog, and is one anthology that is a must for any western enthusiast's

bookshelf.

Tucson, the Gila River, Fort Bowie . . . places mentioned by Chris in his

autobiographical article and his books can also be found on the map at the

front of Leonard's book. Apaches, cavalry, resourceful civilian scouts and

ladies in peril (but who cope) are likewise elements in common.

Also in this edition, we have more facts about horses from a man who has

known and has worked with them for longer than he has been writing western

novels. Greg Mitchell is another who brings a note of authority to his fiction.

And we pick up a debate-provoking piece from the fine historical-mystery and

thriller writer C. S. Harris. We hope it will form the basis for later discussion

by a panel of BHW writers. All this plus new Hoofprints left by the famous

and not-so-famous. . . .

Your comments and western news are always welcome at feedback@blackhorsewesterns.com

|

|

Photo: Freddie Feest

|

How Walt Masterson chased his dreams

BLAME IT ON SUDDEN

When he finds the struggling Wheatley family trying to make it all by

themselves through troubled Apache territory of the Sonora Desert, army scout

John Best begs them to wait for him to guide them. But they set out on their

own and the Apaches strike first.

Now Best finds himself helping the teenager Lucien to rescue his beautiful

sister Emma from a terrible fate. However, the US Cavalry, under a demented,

newly commissioned officer, seems to be determined to complicate matters

instead of riding to the rescue.

It's all down to Best to fight his way through despite the odds.

Back cover

Guns Along the Gila

Discriminating Black Horse Western readers have been warming to the

work of Christopher Kenworthy under the pen-name Walt Masterson. Late last

year BHE tracked him down and requested an interview.

Chris promptly replied, "I was surprised

and delighted to get your email. Yes, I'd be flattered to do an interview.

Since I spent most of my professional life interviewing other people, it

will be a most interesting experience to be on the other end of the process.

I actually wrote my first two westerns back in the 1980s, but left Fleet

Street to go freelance shortly afterwards and, as you will know since you

come from the same background, freelances don't write anything that doesn't

pay top dollar. I retired from professional journalism six years ago, then

came back to the western world a couple of years ago. I enjoy it thoroughly.

. . ."

Recognizing Chris's wide experience, BHE eschewed a rigid question

and answer format, made a few basic suggestions and left it to him to decide

what he cared to tell. The result is this highly entertaining and informative

article. . . .

IT was all Oliver Strange's fault really. In the post Second World War

years, my father and mother, at their wits' end to find a school in which

I would not be swamped by the local lads, sent me off to an English boarding

school perched on the end of the Pennine mountain chain in the mountainous

wilds of Derbyshire. The teaching was gentle, the headmaster, a saintly

man, did not believe in corporal punishmant, and what else can you do

to someone in a boarding school? You can't keep him in, because he already

is. So I did not believe in doing anything I did not actually want to do.

But the school was in a kind of minor stately home. It contained a

magnificent library, and the library contained wall after wall of books.

A child thirsting after knowledge could have done a PhD on the contents

of that library. I thirsted after adventure, and I found it in the great

adventure wrtiters. I read Walter Scott, H. Rider Haggard, everything I

could find about King Arthur and his court and so on. And I discovered the

Sudden novels of Oliver Strange. Night after night I lay in my dormitory

bed, reading by the light of a lamp outside the window, and riding the range

with Sudden.

Sudden led me to Zane Grey, and on and on and on. Louis L'Amour and

I made contact quite a lot later, but we bonded. By this time a professional

journalist in Fleet Street, I did the grand tour of the street, working

for the Daily Express, the Evening Standard, television programme magazines,

the early television column of The Sun newspaper. I managed to interview

a stream of authors parading through London, and I shamelessly looted

their brains and expertise.

|

|

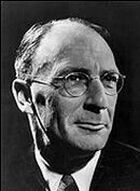

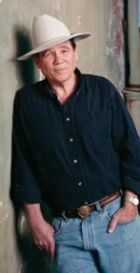

C. S. Forester

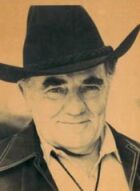

Louis L'Amour

|

C. S. Forester ( I love seagoing adventure, too, of course; Hornblower

and I hit it off splendidly) told me: "Write the books you would want

to read," so I did. I wrote a series of four seagoing adventures set in

the Anglo-American war of 1812.

When I discovered Louis L'Amour, and found he had hundreds of titles

in print, I thought I had achieved paradise. I worked my way steadily

through every word of his that was available at the time. Indeed, so prolific

was he that I am still finding, decades later, Louis L'Amour titles I have

never heard of.

Finally, I actually met Louis. I could not believe my luck. We had lunch

at one of London's top hotels and I don't know about him, but so far as

I was concerned, we bonded. This big man -- he was in his later years

by this time, but still looked as though he had been hacked out of granite

-- sat and poured out his own history and what amounted to a blueprint

on how to write westerns. He even paid for the lunch, against my startled

objections, I swear. I can't remember what we ate, but I consumed what

he said greedily and and laid it all on paper.

There is a curious snobbery about westerns. Literary critics and those

who aspire to letters dismiss them as "pulp westerns". Well, sucks to

them. The late, great Sir Winston Churchill loved them, I am told, and

he was a literary talent of awesome proportions. Me, I'm with Winston.

|

|

|

Promptly

two dust coloured shapes popped up and started their jinking runs, one of

them providentially in his sights, and he saw the blood fly when his shot

hit the man in the head. He went down like a sack of potatoes, though his

companion dived into the ground several yards closer. At this rate they would

be all over him in ten minutes and he knew that he had to move. Trouble was,

so did the Apaches and they began to speed up their charges.

|

|

|

A good western contains everything an adventure story should. It has

a strong action line. It has heroic heroes and villainous villains. It

is, I sometimes think, the last refuge of simple morality. In a good western,

good triumphs. Elmore Leonard's Valdez is Coming is an

outstanding one -- a brutal and powerful man surrounded by hired guns and

bully boys is brought down by a retired Mexican scout who, through his courage,

expertise and sheer doggedness, reduces the villain's band of hired thugs

to a basic minimum, steals his woman and finally humiliates him in front

of the remains of his gang. Good old Valdez! He gets the girl, too.

I asked Louis L'Amour why the West seemed full of tough men on both sides

of the law.

He pointed out that just to get to the western territories before the

opening of the railroads meant months of travel. Most of the people who

started out from the frontiers of civilization walked for thousands of

miles, with their homes in wagons, their wives and children with them.

Kids were born on the trail. People got married.

|

|

Martha Summerhayes

|

Just getting there could kill you. I read the wonderful Vanished

Arizona, Martha Summerhayes' magical first person account of life

as a junior officer's wife in Arizona in the 1870s and 1880s. As a young

bride, she had to get to California, take a steamer to

the Gulf of California, and a paddle steamer up the Colorado to Fort Yuma.

Conditions for the gently born girl from the East Coast were frightful.

At one time during their service in Arizona Territory, she gave birth to

her baby and then promptly had to travel across Arizona in an Army ambulance

-- wagon with springs -- through territory ranged by vengeful Apaches. Her

husband gave her a small handgun and told her to use one cartidge for her

baby and the other for herself if he should be killed in a skirmish. The

ambulance, incidentally, was not provided because she had just given birth.

It was the only available form of transport for women at the time.

Welcome to Arizona, Mrs Summerhayes. Enjoy.

What women they were, the ones who plodded across the continent to make

new lives in the West! They faced everything their husbands faced and more.

And when they got there, the hard work really started. There are accounts

of women pulling their husband's plough. Now that's a woman!

|

|

|

An hour later he was looking down into the contaminated water of the seep.

There was a dead pony lying half in and half out of the water, its throat

slit and a boken cannon bone testifying to the reason it had been sacrificed.

There was no need for the Apache to ambush the site. By their act they considered

they had either condemned their pursuers to death or forced them to break

off the pursuit and return to the last water source.

|

|

|

|

All this knowledge about Arizona and New Mexico came my way when my

son, Matthew, who is an astro-physicist (you don't need to know this but

I like saying it) went to Tucson to work. He has been there for nearly ten

years, now, and we visit him as often as we can, but in any case at least

once a year.

Because of Matt I actually got to visit places I had only read about,

or seen John Wayne defending with unerring aim. My first two westerns,

Carnigan's Claim and A Hot Day In Hammerhead,

were written and originally published under the pen-name of C. Kay (geddit?)

and more significantly, written before I had actually been to the States

at all. We drove around Arizona with my heart in my mouth because I was

sure my ignorance must be apparent in the books . . . and found to my astonishment

that thanks to dear old Duke and his co-stars I hadn't made any glaring

bloopers.

But actually being able to go there brings the whole of the South West

alive in a very special way. The first revelation was that Arizona really

is like that! The Painted Desert really does look as though some

gigantic amateur decorator has been splashing the rocks with weird colours.

The Grand Canyon truly is beyond words. The Sonoran Desert, where I set

Guns Along the Gila, has not changed since the

only way to get to Fort Yuma was to ride a horse, drive a wagon or walk.

Well, okay, there's a magnificent highway through it now, and Yuma is surrounded

by irrigated fields where they grow lettuce, for heaven's sake, by the

square mile.

There really are forests of saguaro cactus -- the ones like men standing

with their hands up -- but they stop growing somewhere north of Phoenix

and a place called New River. There's a growing community there now, but

at one time there was just a refuge for travellers going north to Prescott

and the fort at Camp Verde. General Crook used Verde as one of his bases

during his campaigns against the Apaches. His main headquarters was at

Fort Apache though. It is still there, in a setting of savage beauty,

and so are the Apaches. You can visit Crook's home and stand on the parade

ground. The Apaches watch you with unreadable eyes. It can be unnerving.

It is, after all, their homeland.

|

|

|

"Between

here and Yuma, there's a whole lot of Sonoran Desert. That's bad. In that

there Sonoran Desert there ain't nothing that doesn't sting or poison or

bite."

|

|

|

If you want to go to another fort which really controlled the end of the

Indian wars, you can still see its remains. It is Fort Bowie in Apache Pass

to the south. The reason for the fort is Apache Spring, which was used by

both the Apaches and the white migrants passing through, and constantly fought

over. Cochise used to live nearby and it hasn't, so far as I can make out,

changed at all. The valley which is Apache Pass has a gentle, rising path

up to the spring, and the remains of the fort are beyond it. I've been there

and drunk at that spring, despite the notice advising against it. I couldn't

resist the temptation.

The reason I love Louis L'Amour's work is that he was a genuine westerner

and it shows. Strip out the guns and the horses and what you have in so

many of his books is a story which would be interesting in any setting.

His heroes are real men, and occasionally make real mistakes. When they

get shot -- and they frequently do -- it hurts them and they bleed. Set

afoot in the desert, Hondo Lane doesn't miraculously come across a straying

Indian pony, he humps his saddle and his gear for days before he arrives

at an isolated ranch and then he has to buy a horse and break it himself

before he can get going with his despatches. And, incidentally, meets the

heroine and love of his life.

|

|

|

All he had to do was wait and the night would reveal itself to him. Very

slowly it did so. First the faraway creatures emerged from the black and

silver. A coyote trotted busily along the trail below, stopping now and again

to raise its head and listen and sniff the air. It could probably, Best knew,

smell both him and the horse. What tiny wind the night allowed to whisper

over the land carrried a river of scents on it, rich and pungent to the wild

nose out there.

|

|

Ruger Single Six

|

Why choose Walt Masterson as a pen name? "Walt" is a friend of mine

in Tucson who once worked as a guide in Tombstone, so he actually did walk

down Allen Street wearing a Colt on his hip. He has a fine collection of

weapons, including a Winchester carbine, and Colt .45, so I know what they

weigh and how they feel. In my youth, before privately owned handguns were

outlawed in Britain, I owned a Ruger Single Six and went target shooting

every week. Better than carrying a gun in Tombstone. The targets don't shoot

back.

"Masterson" is in honourable memory of Bat Masterson who was in Tombstone

with the Earps and went on to become a newspaperman. I was slightly embarrassed

to discover there really was a Walt Masterson, related to Bat, but I

don't think I have done anything to embarrass him.

I have a whole collection of books about the history of the South West,

and a pile of newspapers and magazines both from the period and recalling

it. Many of my stories -- Guns Along the Gila is one -- are

based on real stories of real people. Considering what they did, and how

they lived and survived, it is impossible to exaggerate.

They haven't changed much either. The cowboys in the white hats --

and yes, they do wear them, though these days they often ride pickup trucks

rather than mustangs -- talk the way they do in films, and wear blue jeans

and western shirts. Why not? They are cowboys and they live in the West.

I know, I know, I go on about the West. Its brief history fascinates

me, the country itself draws me, the people charm me.

And now, if you will excuse me, I must get back there. There's

a small wagon train crossing the Painted Desert on the old Mormon Trail,

running into trouble with four crooked brothers and I need to get the

hero down out of the mountains to give the people a hand. I have a feeling

gunplay is in the offing. . . .

|

|

|

|

|

Under many brands. Under many brands.

|

A new set of western tracks

HOOFPRINTS

Veteran author Keith Hetherington, of Queensland, Australia,

tells Hoofprints, "Ran into a bloke I haven't seen for a while in the local

library and he told me he picked up a Brett Waring Cleveland paperback from

a book exchange last week -- 'Hey, mate! Thirty bloody years old and she's

still a good yarn! You better tell me the pen-names you use now.' I did,

and he already had a Jake Douglas BHW in his bag and went off to look for

more under my pseudonyms. Bit of a lift . . . in fact, apart from movie

sales, just the thing to pick you up." Regular BHW readers won't need reminding

that Keith's other BHW bylines are Clayton Nash, Hank J. Kirby and Tyler

Hatch. And as reported here in our December 2006 number, a nickname he also once

had was "Ringo", which pops up in the title of his latest book. Publisher

John Hale describes Call Me Ringo as "a splendid western". This is something

of a relief to Keith since he put it together last (southern) winter while

battling a bad case of flu and longer-term health woes despite

having had an annual anti-flu vaccination. "I've never felt so low,"

he said then. "Don't know where I am half the time or what I'm doing."

As in a good Hetherington yarn, all's well that ends well!

|

|

|

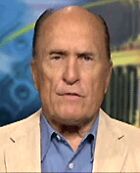

Actor Sam Elliott has carved a niche playing

men who adhere to a cowboy code of honour. He told Susan King in an interview

for The Scotsman how his childhood was spent in suburban Sacramento but early

roles in westerns kept coming his way. "I have no explanation for it.

It's not like I went after them necessarily. . . . My family on both sides

for several generations all hailed from Texas. My dad was with the Fish &

Wildlife Service and got transferred from West Texas to Sacramento. I was

born the year after they got there. I never heard the end of the fact I

wasn't a Texan." But Sam spent a lot of time around ranchers and

real-deal cowboys and sheepmen. "There is something about that sensibility

in general that appeals to me." Today Elliott lives in the wilds

of Malibu and owns a ranch, complete with horses, south of Portland,

not too far from where his 92-year-old mother resides. Meanwhile, at

Hollywood.com, staffer Scott Huver noted that 2008 marked the 63-year-old

actor's fourth decade in films and television. "You had a good,

long association with author Louis L'Amour -- projects like The Sacketts,

The Shadow Riders and Conagher. Any more of his works that you'd like

to do?" Sam replied, "There are a couple more . . . I think Tom Selleck

has the rights to one of them. . . . I love L'Amour's stories and his

characters. They're so classically American westerns and cowboys. That's

the kind of stuff I really love doing. That's kind of the ultimate escape

on some fantasy level."

|

When is a Texan not a Texan?

|

A broken wing.

A broken wing.

|

Chris Kenworthy found putting the finishing touches to his fine leading

article for this edition of BH Extra a somewhat challenging exercise. Just

days before Christmas, he fell and broke his left arm. This gave him plenty

of time to read his emails at what should have been a more active time of

the year -- "I'm restricted to the house and my right hand" -- but among

the disadvantages were the many minutes it took him to prepare replies to

the messages. He hopes to contribute to BHE again, "hopefully a good deal

faster than currently . . . this reply is being typed with one finger at

a pace which would bore a snail with its ankle in plaster." Fortunately,

the next Walt Masterson BHW, Gunfight at Dragoon Station, was all complete

and is safely scheduled for publication on May 31.

|

|

|

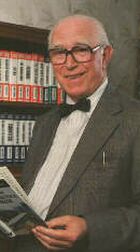

Robert Duvall is another actor closely associated with westerns. He starred in Open Range and two of television's

most celebrated treatments of the genre, Lonesome Dove and Broken Trail. An interviewer for the Basingstoke Gazette asked him, "Where does your love of

the genre come from?" He said, "It's our deal. The English have Shakespeare, the French have Molière

and the western is definitely ours. When I was a kid I went to my

uncle's ranch in Montana for two summers -- he had a big cattle and

sheep place out there. And you know, when I first went to Hollywood

I would take out a horse every day -- bareback, English saddle, western

saddle -- and I learned to jump a horse, so I would have a seat on a horse,

because most actors can draw a pistol but they can't ride a horse. So I

wanted to do westerns and it served me well. So I think westerns are our

thing. People say they don't sell, but they do sell and, as soon as you

make them, they say, when are you going to do another one? In England, they

love westerns, wide-open spaces and all that. I just like doing them."

He laughed. "At the end of my career I thought maybe I could do a gunfighter

in a western who is mute, so I wouldn't have any lines."

|

"Definitely ours."

"Definitely ours."

|

The late Mr Paine.

|

Hoofprints has quoted in the past at least one brother writer who believes

his BHWs will allow him to achieve a sort of immortality. What better,

then, than to go a step further to what, at first glance, looked suspiciously

like reincarnation and a sex change! In the December issue of its magazine

Roundup, Western Writers of America featured a review by Linda Wommack

of a Five Star publication, Man From Durango; A Western Duo by Lauran

Paine. As David Whitehead has told us in an informative BHE article

(December 2006), visit any library in Britain and Paine (1916-2003)

is still the best-represented western writer on the shelves -- thanks

largely to a record output of BHWs under his own name and dozens of pen-names.

The Roundup review told its specialist audience, "Lauran Paine is undoubtedly

one of today’s greatest Western fiction writers. With dozens of books to

her credit, including the bestseller Open Range, also a major motion picture

hit, the latest book, Man From Durango, gives fans two tales in one volume.

. . ."

|

|

|

At the website of the Madison (Wisconsin) Public Library, Robin of Meadowridge

reviewed Cormac McCarthy's All the Pretty Horses and added in a footnote:

"I had always thought of westerns as, well, just westerns, until a library

tour guide informed my group that only older men read westerns. And furthermore,

that her library (not a library in our system, thank goodness) was only

allocating one spinning rack to western paperbacks because 'everyone

who reads westerns is going to be dead soon'. I bristled, and still bristle when I recall it eight years later."

|

Madison library corner. Madison library corner.

|

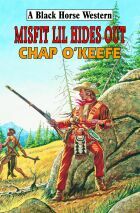

Lil . . . is she PC?

Lil . . . is she PC?

|

In a lively debate at the Piccadilly Cowboys forum, Maestro, of Illinois,

told Steve M, "My opinion on Ralph Compton westerns -- thumbs down! The writing

is juvenile to the extreme and the books are filled with modern-day political

correctness -- rootin tootin female gunfighters galore! Something that

never even came close to reality back in the Old West. . . ." Mick Keetley,

of Derby, England, responded, "The ones I have read do not have female gunfighters."

Then BHWs' Chap O'Keefe, maybe with an eye to championing Misfit Lil,

pitched in. "I can't speak for the works of any of the 'Ralph Comptons',

but rootin' tootin' female gunfighters sound like a great chance for some

fun to me. And I can't agree that they have much to do with modern-day political

correctness. Tough western heroines have a tradition that dates

right back to the Beadle Dime Novels featuring Hurricane Nell, Calamity

Jane and others. For this genre, how much further can you go? You're quite

right that sassy ladies weren't part of the everyday reality of the Old

West, but was much of what we read and enjoy? For myself, I find writing

the Misfit Lil series has given me a chance for a break from more

seriously researched books like Peace at Any Price." Dipping into the latest Lil, Misfit Lil Hides Out, Hoofprints finds a chapter beginning, "It

seemed doubtful the ball at Fort Dennis could afford any excitement more

irregular than the spanking of Lilian Goodnight." A gruesome murder is then

committed. Politically correct? Hmm. . . .

|

|

|

Demand is growing for large-print books, Johanna King reported in the Albuquerque

Journal (New Mexico). "Whether travelling, exercising, suffering from waning

eyesight or just plain tired, large-print books may prove to be a saving

grace for readers. The large typeface in the books makes them easier to read,

and not just for the visually impaired. Large-print titles are gaining

popularity among commuters and travellers being jostled by planes, trains

and cars, say librarians and booksellers. They note the books are also

the choice of office workers whose tired eyes can’t focus well after spending

all day staring at a computer. And they’ve become part of the exercise

arsenal for gym enthusiasts who read while working out on treadmills and

stationary bikes."

|

Time for an eye-opener?

Time for an eye-opener?

|

Thorpe's top-shelf westerns.

Thorpe's top-shelf westerns.

|

The distinctive T&P tepee stamp on magazines imported by the Thorpe

and Porter firm of Oadby, Leicestershire, was a familar sight in Britain in

the 1950s and gave many readers their first taste of western and other pulp

fiction from America and Australia. After principal Frederick Thorpe

retired from the business, he hit on an idea for helping elderly and impaired-sight

readers. In 1964, he founded large-print book publishing in English, reprinting

old favourites in editions about twice the size of the regular books.

The books had no cover art and were color-coded to indicate categories

-- like orange for westerns, black for mysteries -- a convention that

has survived on the spines to this day. In 1969, Thorpe's Ulverscroft company

began to retypeset the books in 16-point type and put them in normal-size

bindings, increasing acceptance by ordinary public libraries. Thorpe

became a large-print ambassador, travelling the English-speaking world promoting

the provision of large-print books for seniors. Today, Ulverscroft continues

to issue westerns under the Linford and Dales imprints -- a large percentage

being reprints of the best recent BHWs.

|

|

|

Just published is newcomer Matthew P. Mayo's second BHW novel, Wrong

Town, in which homely-faced hero Roamer strives to save the Rocky Mountain

township of Tall Pine from tearing itself apart. Matthew is also the editor

of, and a contributor to, Where Legends Ride, a 14-story anthology published

by a group of writers operating under the badge Express Westerns. And he

has his very own, tastefully designed author website. But Hoofprints can

only wonder why his home page -- at which he offers his services as an editor

and writer -- features a photograph of a chimpanzee working at an old-fashioned

manual typewriter. Is it a picture of the proud author? What he expects

to be an uncle of if you take up his offer? Or is it a subtle suggestion that

anyone who pays peanuts must expect a monkey? The puzzle's

too deep for Hoofprints! We'll be looking out for Matthew's books instead.

. . .

|

Monkey puzzle.

Monkey puzzle.

|

Different outlaws.

|

Several BHW authors have been moving into new stalls at the Robert

Hale publishing stable, making forays from the Old West on to the crime

and historical scenes where the company is strengthening its presence.

They include John Paxton Sheriff (aka Jack Sheriff, Matt Laidlaw, Jim Lawless

and Will Keen), Keith Souter (aka Clay More) and Jean Rowden (aka Eugene

Clifton). Keith Souter's latest title is The Pardoner's Crime. It is the

time of outlaw Robin Hood and Sir Richard Lee, Sergeant-at-Law, has been

sent to Sandal Castle by King Edward II to preside over the court of the

Manor of Wakefield. Within hours of his arrival, Sir Richard and his assistant,

Hubert of Loxley, are forced to investigate a vicious rape and a cold-blooded

murder. . . . It appears Keith is staying closer to home. He graduated in

medicine from the University of Dundee and has worked as a family doctor

in Wakefield for many years. He tells us, "I live within arrow-shot of historic

Sandal Castle."

|

|

|

Author Ray Foster (aka Jack Giles) had a great 2007, getting back in the

writing saddle after an eight-year hiatus. Virtually on Christmas Eve, he

emailed us, "Just today heard back from Robert Hale -- there will be a new

Jack Giles western titled Lawmen. Absolutely, thrilled to bits. What a

Christmas present. . . ." For those who do not already know, Ray explains

for BHE in his own words: "Jack Giles, figuratively, 'died' in 1999 halfway

through two books -- whether he gets 'resurrected' is a matter of debate.

In 1999 I had a stroke -- and, although I can walk, talk and do things

that 'normal' people can do, I did lose near enough 30 years of memories.

Of course, one of the first westerns that I read was a Jack Giles and my

wife, gently, had to break it to me that I had written the book. The story

of how I came to write westerns was documented; the original contracts were

in a file along with a couple of letters from Terry Harknett [aka Edge author

George G. Gilman]."

|

Jack rides again.

|

|

|

|

|

Finally! The low-down on how writers work

OF PLOTTERS AND PANTSERS

BHE has borrowed advice for writers from Candy's Blog before. CANDICE

PROCTOR writes a Regency mystery series under the name of C. S. Harris and

thrillers as one half of Steven Graham. Her blog posts contain considerable

good sense for all writers. They also widen our appreciation as readers.

Recently,

Candy said she thought respect was "the single most important aspect of powerful

writing . . . . Respect for one’s craft, respect for oneself as a writer,

but most importantly, respect for one’s readers. This is what drives me to

spend days researching an elusive fact, that inspires me to deepen my characters,

to polish my prose, to close up my gaping plot holes, to plumb the depths

of each scene’s emotional potential. It’s because I respect my readers and

my craft that I strive always to avoid the overdone, the hackneyed, the melodramatic;

that I don’t let myself take the easy way out, that I always push myself to

reach that little bit further."

Here is a past post on Plotting that BHE hopes it will be possible to follow

up with a panel discussion among BHW writers.

WRITERS typically fall into one of two camps: those who plot their books

before they begin, and those who do not.

The latter types like to live dangerously and fly — or rather, write —

by the seat of their pants. Believing that advance planning kills their muse

and destroys their interest in a story, they jump in with little idea of

where their story will go. In a romance, they’ll start with a “cute meet”

and fumble their way forward from there. In a mystery, they don’t know ahead

of time who will turn out to have committed the murder or why; sometimes

they’re not even sure who — amidst all the characters magically appearing

on their pages — will actually be the one to fall victim to a foul deed and

start the mystery rolling.

|

|

James Lee Burke

|

In the hands of a master, this “winging it” approach can be highly successful:

James Lee Burke, for instance, says he can never see more than two or three

scenes ahead as he writes, yet what he produces is brilliant. Unfortunately,

with many “Pantsers”, the result is all too often a wandering storyline,

gaping plot holes, an unbalanced story arc, and a host of other dastardly

results.

As you can see, I’m not a fan of this approach. Yes, it can work, and

work well. Yes, there are bestselling writers who use this approach. But

then, there are a lot of books published every year — including bestsellers

— that I find just don’t hold my attention. And you know what? I’ve discovered,

after a little bit of digging, that most of the writers whose books I put

down are Pantsers rather than Plotters. Now, that might tell you more about

me as a reader than anything else — unless I’m reading something beautifully

literary, I like a tightly knit, well-constructed book with a good story arc.

There are obviously many readers who don’t mind a more rambling, casual,

disjointed tale. The Pantsers are for them.

|

|

|

If a recent discussion on the DorothyL mystery listserv is anything to

go by, a surprising number of mystery writers — like romance writers — use

the Pantsers’ approach. There seems to be something about the act of plotting

out a story in advance that kills their joy in writing it. Some Pantsers

do massive rewrites to pull their ramblings into something cohesive — and

publishable. Others seem to be able to plug into their subconscious so successfully

that they claim their books require almost no rewriting. There’s a lot of

New Age-like talk about whether Plotters are left-brained or right-brained,

but the discussion is seldom flattering to the Plotters. Plotting is often

portrayed as plodding and pedestrian; the antithesis of creative; Pantsers

typically see themselves as the truly creative ones, giving birth to an

almost mystical product.

Frankly, I’ve never been able to decide if I’m left or right brained.

I am very analytical, very methodical — I was, after all, an academic. Yet

I’m also very creative — for many years I planned to become a professional

artist. One of the reasons I like plotting my books out in advance is that

it gets all that analytical stuff out of the way, so that when I sit down

to actually write, I can just relax and let the story flow without worrying

about structure.

Incidentally, there is a third kind of writer. These people never plot

anything out on paper, and they don’t use notecards or post-it notes. But

they’ve given so much thought to their story before they begin that they already

know their story arc, their key scenes and major characters. They may not

be plotters in the traditional sense of the word, but I don’t think they

can really claim to be writing by the seats of their pants, either. They

just have amazing memories. I’m not one of them.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Greg Mitchell checks the facts

MORE HORSE TALK

(With quotations from the classic book The Log of a Cowboy by Andy Adams, first

published in 1903. Greg Mitchell says, "His book is a very good one

with plenty of reference material for writers. The size of some of those

old trail herds was amazing. The biggest mob of cattle I ever worked with

was slightly over 1,500 head and that was roughly a mile from the leaders

to the tailers. Adams' herd was 3,000 head, so on the road they would stretch

out to nearly two miles.")

THE cowboy's horse may have been his best friend but it can be a western

writer's worst enemy if it is wrongly described or used for doing the impossible.

Get the horse details wrong and they can destroy the author's credibility.

And don't think that most readers won't pick it up. Many western readers

are horse people and though riding styles might differ from country to country,

some facts about horses remain the same.

Here are a few fictional clichés and the reality.

Riding horses

As mentioned in the December 2007 edition of Black Horse Extra, stallions

are poor choices for general riding. They can be bad-tempered and if a mare

in season is nearby many are difficult to control. Good stallions were kept

mainly for breeding purposes and were often too valuable for day-to-day knocking

about. While an outlaw might steal one to escape the law or to use for one

specific task, it would be too dangerous to keep the horse for any length

of time. The task of taming a mature wild stallion would be beyond the ability

of the average rider and even when tamed, such animals would still be difficult

to handle and unreliable in performance.

Likewise, draughts are not much good because their body shapes are wrong

for riding. The problem of a heavy rider is not solved by putting him on a

draught horse. A properly built riding type, though hundreds of pounds lighter,

is more capable of carrying weight at speed. It is not a case of the bigger

the horse, the stronger it is. Conformation and breeding are the most important

factors for weight-carrying and endurance.

While the six-feet-two traditional hero might ride a 17-hand horse, such

animals were not common in the West, nor were they any better because of their

size. A hand measurement is 4 inches or about 10 centimetres. A horse's height

is the distance between the sole of the forefoot and the top of the wither

(where the neck runs into the shoulders). A pony is a horse below 14 hands

2 inches, although cowboys often referred to all horses as ponies. Most working

ranch horses would be somewhere between 14 hands 2 inches and 16 hands.

To carry weight at speed, a horse has to be built in a certain way. The

draught horse is not designed to be ridden and will fail quickly if galloped

under a rider. A properly built riding type of 15 hands is a better weight

carrier than the draught.

|

Wild stallion

|

|

At

no time in my life, before or since, have I felt so keenly the parting

between man and horse as I did that September evening in Montana.

|

|

|

I read one western where a large villain rode a Clydesdale draught. It might

have been strong when taken at a walk but would be too slow, too clumsy and

lack the endurance for a true villain's horse. It is a bit hard to lay waste

to the countryside on a horse that is slow and stumbling and scarcely able

to gallop 300 yards.

Arab horses, Morgans and Quarter horses are not tall and 15 hands is

considered a fair height for such breeds. Very tall horses usually had Thoroughbred

or draught in their breeding.

Mustangs had a reputation for toughness, and some of these were only

about 14 hands but they were not particularly good weight-carriers because

of their small size.

Travelling

When fit, a good riding horse can easily cover 40 miles per day but to keep

up that rate over long periods, it needs to be hand-fed and rested for at

least one day a week. Horses are capable of covering much greater distances

in a single day, but it takes its toll on them and sometimes they are not

fit for the next day's work. A good travelling pace that kept the horse in

good condition was 5 miles per hour. It does not sound like much but takes

a lot of trotting and cantering to maintain that rate.

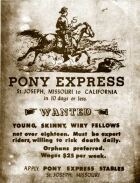

The Pony Express rode at a very fast rate but used, lightweight riders,

specially selected, well-fed horses, and frequent changes of mounts.

Stagecoaches averaged between 9 and 10 miles per hour under normal conditions,

with horses changed every 12 to 15 miles.

Flanks

These really get writers into trouble. In military terms, the flanks are

simply the sides but with an a horse they are a specific place. Flanks are

the areas between the last ribs and the hind legs.

Horses are sensitive around the flank and most riders do not spur them there.

I read of one hero who rode hard "with knees pressed into the horse's flanks".

To do this he would need to be sitting behind the saddle and the horse would

probably buck at such treatment.

Most spurring is done on the horse's sides, not its flanks. A long-legged

rider or one with long-necked spurs could reach the flanks but that is hard

on the horse. A light touch with the spur on the side usually produces a

better result.

Neither horses nor cattle are branded on the flanks.

|

Clydesdale

|

|

For on the trail an affection springs up between a man and his mount that is almost human.

|

|

|

Steering horses

Western stories frequently have riders "kneeing" their horses in all directions.

Horses are steered by the reins or sometimes by shifts in weight, touches

from the heels, or even the calf of the leg but never by the knees. Knees

are mostly used for gripping but not for steering.

Reins are traditionally held in the left hand when riding one-handed. This

not only leaves the rider's right hand free to do other things but allows

greater control over the horse when mounting and dismounting.

Riding styles

Working riders ride differently to today's show-oriented riders and what

is correct in one place can be downright dangerous somewhere else. The bridle

is the main means of control and with horses raised on the open range, it

is the first thing on the horse and the last thing off for safety reasons.

In England and Europe, horses are usually tied up with halters for saddling

so the saddle goes on before the bridle. Authors often mention horses being

saddled in the wrong order.

In England and Europe, riders dismount by removing both feet from the stirrups

and sliding off. This style is fashionable because of small women riding

big horses who have too far to step down from the stirrup, but no self-respecting

cowboy would do it because of loss of control and the chance of being cow-kicked.

Range-raised horses that are feeling energetic or frightened sometimes kick

forward with the hind leg, as a cow does, and will catch the rider who has

just slid off. Others will try to pull away and if they succeed can really

flatten and possibly kill a rider with a straight-back kick from both hind

feet.

Dismounting by the stirrup, if done properly, puts the rider beyond the

reach of a cow kick and allows a greater control of the horse. Because the

range rider often worked alone with dangerous horses, he used different methods

to those of England and Europe. So what is right in one place can be wrong

in a western situation. One author made a point of saying that "professional"

riders never tied horses by the reins. Professional show riders might not,

but working horsemen certainly did. Unlike show riders, their horses were

trained not to pull back and would stand for hours secured in this manner.

It takes very strong equipment to hold any horse in a place where it does

not want to be, so proper training is important.

|

|

|

Every

privation which he endures, his horse endures with him -- carrying him through

falling weather, swimming rivers by day and riding in the lead of stampedes

at night, always faithful, always willing and always patiently enduring every

hardship from exhausting hours under saddle to the suffering of a dry drive.

|

|

|

Rearing horses

These are favourite means that writers use to separate riders from

horses, but the hero should not fall off a rearing horse as rears are not

hard to ride. An unexpected shy or a buck can be much harder to sit.

Horses do not rear if they see a snake. This writer has personally seen

two cases where horses stepped on snakes and did not react in any way. They

might have if the snakes had bitten them, but they seemed oblivious to the

reptiles' presence. Sighting the sudden movement of a snake might make a

horse shy but they do not rear or bolt.

Bucking horses

These were common in the West for various reasons but writers talk of horses

bucking for impossibly long periods. Bucking time is measured in seconds

rather than minutes. Bucking requires a great amount of energy and it is

a very good bucker that can buck hard for 10 seconds . Some will stop to

recover their breath and start again but they cannot keep going continuously.

A cowboy used to riding, who has a decent saddle, does not get saddle-sore.

Open wounds sometimes described, would not occur with the usual western

saddle. They are designed for rider comfort during long working days. Only

under unusual circumstances do experienced riders get saddle-sore.

Side-saddles, lame horses

Most ladies in the Wild West era rode side-saddle. A few rode astride but

it was considered unladylike and few did it in public.

The loss of a shoe does not automatically lame a horse and many ranch

horses were not shod. It just depended upon the country where they worked

and how much work they were given. Stone bruises are too often trivialised

in stories as being nothing very serious. Any stone bruise will put a horse

out of action once the injury cools. These bruises are very painful and in

the days before antibiotics, some took a year to get right. Tendon damage

is usually serious and in some cases permanent. Liniment was used on sprains

but was never used on open wounds.

Shot horses

Horses are large, powerful animals and can absorb quite powerful bullets

without being knocked off their feet. Most comparatively low-powered firearms

of the Wild West era would not kill a horse outright unless it struck the

brain or penetrated to the heart. A brain-shot horse drops immediately,

but one shot in the heart can gallop fifty yards or more before collapsing.

It was possible to empty a revolver into a horse with no apparent damage

to it although the animal would probably die a slow death later.

|

|

|

When the shooter is some distance from the horse, it is possible to hear

the sound of the bullet striking the animal.

Though we sometimes laugh at situations where heroes are rescued by their

faithful horses, a few such animals exist. In this old bloke's lifetime

I have had two horses that were fiercely protective of me and would attack

any horse or dog that they thought might harm me. Any human who threatened

me might also have found himself in trouble but such occasions never arose.

So protective horses do exist but they are not common. I doubt if either

of mine would have been smart enough to chew through ropes or do some of

the things that fictional heroes' horses sometimes do. I had another that

was very loyal to the extent that she defied the herd instinct and stayed

with me when other horses galloped away. But the majority of horses do not

show great powers of reasoning. Most are content to do the horse's job and

leave thinking work to others better qualified. Where horse and rider have

had a close association, it is possible that the animal might do something

unusual to protect the man, but remember -- horses are not Rhodes Scholars.

The western character is incomplete without a horse and these wonderful

animals can greatly enhance a story if references to them are correct. If

a writer is not sure about some aspect, it is safest to use general terms

rather than go into details that might sound right but do not really suit

the situation. It is a case of "different strokes for different folks". What

is right in show riding can be wrong or even dangerous in western situations.

Don't rely on the wrong books when doing research!

-- Paddy Gallagher, aka Greg Mitchell, whose next BHW,

Range Rustlers, will be published in April.

|

|

|

|

|

|

NEW

BLACK HORSE

WESTERN NOVELS

Published by Robert Hale Ltd, London

978

| Call Me Ringo

|

Hank J. Kirby

|

0 7090 8531 7

|

| Wrong Town

|

Matthew P. Mayo

|

0

7090 8511 9

|

Duel at Murphy's Ford

|

Tom Benson

|

0

7090 8519 5

|

The Long Chase

|

Alan Irwin |

0

7090 8527 0

|

Tough Justice

|

Skeeter Dodds

|

0

7090 8502 7

|

Saratoga

|

Jim Lawless

|

0

7090 8539 3

|

A Reckoning at Orphan Creek

|

Terrell L. Bowers

|

0

7090 8525 6

|

Misfit Lil Hides Out

|

Chap O'Keefe

|

0

7090 8352 8

|

Hell's Courtyard

|

Corba Sunman

|

0

7090 8491 4

|

Six Days to Sundown

|

Owen G. Irons

|

0

7090 8532 4

|

In the Name of the Gun

|

Ryan Bodie

|

0

7090 8543 0

|

The Death Trail

|

M. Duggan

|

0

7090 8545 4 |

Renegade Gold

|

Robert Anderson

|

0

7090 8547 8

|

Duel at Cheyenne

|

Daniel Rockfern

|

0

7090 7687 2

|

Blood Creek

|

Lance Howard

|

0

7090 8454 9

|

Wolf Hole

|

Abe Dancer

|

0

7090 8544 7

|

Lightning at the Hanging Tree

|

Mark Falcon

|

0

7090 8553 9

|

Temptation Trail

|

Billy Hall

|

0

7090 8554 6

|

Range Rustlers

|

Greg Mitchell

|

0 7090 8567 6

|

|

|

|

Black

Horse Westerns can be requested at public libraries, ordered at bookstores,

and bought online through the publisher's website, www.halebooks.com, or retailers including Amazon, Blackwells,

WH Smith and VinersUK Books.

Trade inquiries

to: Combined Book Services,

Units I/K, Paddock Wood Distribution

Centre,

Paddock Wood, Tonbridge, Kent TN12 6UU.

Tel: (+44) 01892 837 171 Fax: (+44)

01892 837 272

Email: orders@combook.co.uk

For Australian Trade Sales, contact DLS Distribution Services, tradesales@dlsbooks.com

For Australian & New Zealand Library Sales, contact DLS Library Services, swalters@dlsbooks.com

DLS Australia Pty Ltd, 12 Phoenix Court, Braeside, 3195, Australia.

Ph: (+61) 3 9587 5044 Fax: (+61) 3 9587 5088

|

|

|

|

|

|